Getting to know your data

Learning Objectives:

What's the goal for this lesson?

- You should be able to identify common features of "data" and data formats and what those features imply

- You should be able to look at a file and be able to identify the following types of data: fasta, fastq, fastg, sra, sff, vcf, sam, bam, bed, etc…

- You should be able to identify where your data came from (provenance)

At the end of this lesson you should be able to:

- Recognize file formats

- Whether your data files are zipped or unzipped. You should have an understanding of file compression.

- How to determine the file size

- How many units are in the file (i.e. nucleotides, lines of data, sequence reads, etc.)

- How to look at data structure using the shell – does it agree with the file extension?

- Identify a binary, flat text file?

The following table shows some of the common types of data files and includes some information about them:

| File Extension | Type of Data | Format | Example(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| txt | multi-format | Text | study metadata, tab-delimited data | txt |

| fastq | nucleotide | Text | sequencing reads | fastq |

| fasta | nucleotide, protein | Text | the human genome | fasta |

| sff | nucleotide | Binary | Roche/454 sequencing data | sff |

| vcf | multi-format | Text | variation/SNP calls | vcf |

| sam | alignment | Text | reads aligned to a reference | sam |

| bam | alignment | Binary | reads aligned to a reference | bam |

| bed | metadata / feature definitions | Binary | genome coverage | bed |

| h5 | binary hierarchical | Binary | PacBio sequencing data | h5 |

| pileup | alignment | Text | mpileup, SNP and indel calling | pileup |

Looking at the data for this workshop

In this workshop, there are a few bioinformatics-related data types we will focus on (beyond simple text files - although in principle many of the files are text). First let's consider the definition/documentation for these file types:

Plain-text

- fastq - definition

- sam file - definition

- vcf file - definition

Compressed/binary

- zip file - definition

- bam file (binary sam file) - definition

md5sum

In addition to understanding how to work with these files, we also need to understand how to verify the integrity of these files. It is not uncommon to download a file, and get error messages, have to restart downloads, move files, etc. In these cases, knowing how to verify that two files are the same (not simply named the same) is very important. To do this we use a process called checksums:

According to wikipedia a checksum is 'a small-size datum from a block of digital data for the purpose of detecting errors which may have been introduced during its transmission or storage.'In other words it is a result we can generate that uniquely corresponds to a file. Any change to that file (adding a space, deleting a character, etc.) will change the file's checksum.

Exercises

###File integrity - download a file and verify the download

Working with genomics files almost always requires using the shell, so although this isn't the official shell lesson, we're going to use many BASH functions. If you've already covered the shell lesson, consider this a refresher.

First we're going to download a zip file that is saved in a public

Dropbox folder. We're going to download using either wget or

curl and which one you need to use depends on your operating system,

as most computers will only have one or the other installed by default.

To see which one you have:

$ which curl

$ which wget

which is a BASH program that looks through everything you have

installed, and tells you what folder it is installed to. If it can't

find the program you asked for, it returns nothing, i.e. gives you no

results.

On OSX, you'll likely get:

$ which curl

/usr/bin/curl

$ which wget

$

Once you know whether you have curl or wget use one of the

following commands to download the zip file:

$ cd

$ wget https://www.dropbox.com/s/d7zitckb5fz8494/GenomicsLesson.zip

or

$ cd

$ curl -LO https://www.dropbox.com/s/d7zitckb5fz8494/GenomicsLesson.zip

Most genomics files that you download will be very large, which can make them more prone to download errors. Flaky internet can make you think that your file is finished downloading, even if it really just stopped partway through. Furthermore, even the files that are filled with familiar characters are nearly impossible to fact check by eye. Imagine trying to make sure your favorite genome had downloaded correctly by manually comparing each base on your computer to the one at NCBI. Luckily theres a better way.

Whenever you download a large or important file, you should check to make sure that it is an exact match to the copy online. The most common way to do this is to run the file through a cryptographic hash function which processes all of the information in the file through a complex algorithm to get a hash value. A hash value looks a bit like an ideal password: a random looking mix of letters and numbers. Because the hash function is a very complex equation, in theory, for any given hash function, every unique input will have a unique hash value. So if you get the same hash value from two different files, those files are identical.

There are many available hash functions, and as computers get more sophisticated, older ones become easier to hack, so there will likely alwasy be new ones. But right now, we're going to use MD5 because it is pre-installed on most computers, and is most likely the one your sequencing facility or collaborator will send you when they give you large files.

There are two common versions of MD5, and we're going to use which

again to see which one you have installed:

$ which md5

$ which md5sum

Then get get the hash value for the zip file you downloaded by running either:

$ md5 GenomicsLesson.zip

or

$ md5sum GenomicsLesson.zip

The file I uploaded gave this answer:

$ md5 GenomicsLesson.zip

MD5 (GenomicsLesson.zip) = e237e30985867e6bea741949e42a0c3b

Practice: Download the best practices file from Data Carpentry: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/ACharbonneau/2016-01-18-MSU/gh-pages/Files/GoodBetterBest.md

###Working with Compressed files

As previously mentioned, genomics data files tend to be large. Since larger files are slower and more costly to move around, you will often encounter files that have been compressed to save time/space/money. The two most commonly encountered types of compressed files are Zip archives (e.g. filename.zip), Gzip archives (e.g. filename.gz) and Tarballs (e.g. filename.tar or filename.tar.gz).

Once you've convinced yourself that the file you have is the file that you ought to have, the next thing that you'll want to do is unzip it (a.k.a. uncompress or decompress or extract). You can unzip your .zip archive using the unzip program:

unzip <filename.zip>

If you don't want to extract everything, but rather check the contents, you can view what a zip contains using the -l flag ('list'):

unzip -l <filename.zip>

When you want to go in the other direction and make your own archive the command is simply zip. It works like this:

zip <mynewarchive.zip> <myfirstfile.txt> <mysecondfile.sam>

Note that you can also use the -r flag (recursive) to zip up a folder and all its contents, including subfolders like so:

zip -r <myproject.zip> myproject/

If you have been sent a big bundle of data as a gzip archive, then happily the same procedure applies for viewing and extracting as with zip archives, but with the gunzip program:

gunzip -l <bundle.gz>

gunzip <bundle.gz>

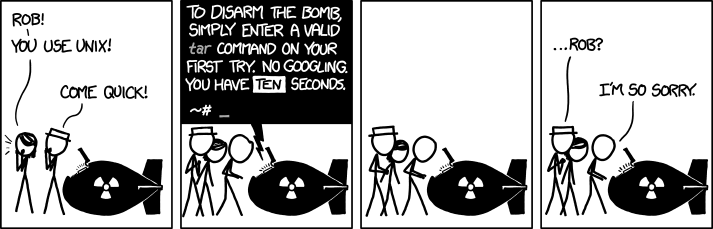

Things are slightly different (read 'complex') if you encounter a tarball: thisfile.tar or thatfile.tar.gz or tacofile.tgz.

You can view the contents of tarballs using the tar program:

tar -tf <thisfile.tar>

tar -ztvf <thatfile.tar.gz>

tar -ztvf <tacofile.tgz>

…and extract them like this:

tar -xf <thisfile.tar>

tar -zxvf <thatfile.tar.gz>

tar -zxvf <tacofile.tgz>

Other types of compressed files and archives do exist, but these are the most common.

Genomics Text files

First, lets see what data files we have available:

ls

ls stands for list, and if you call it all by itself, it just returns a list of whatever is inside the folder you're currently looking at. You should give you a fairly big list of files in alphabetical order. However, they're hard to understand like this, so lets ask ls to make the list a little easier to read:

ls -lah

Here we've added modifiers to ls. Computer people usually call these modifiers 'flags' or 'arguments', and here we've added 3 flags:

-l directs ls to give us the results in 'long format' so we get more information

-a tells ls to show us 'all' of the things in the folder, even if they're usually hidden

-h makes the output 'human readable', so you see file sizes in kb or gb instead of bytes

FASTA

You're likely already familiar with FASTA files, as this is the most common way to distribute sequence information. Let's look at one:

head Raphanus.fa

head is another program, and it shows you just the top few lines of a file. By default, it shows ten, (so five sequences) but we can also change that behavior with flags:

head -4 Raphanus.fa

Now, you should see the first four lines of the Raphanus.fa file.

Exercise >Try looking at EV813540.fa

FASTA files always have at least one comment line, which almost always begins with ">", but can start with ";". A given sequence in the file is allowed to have multiple comment lines, but they usually don't. Extra comment lines for sequences can break some downstream processes.

After the comment line is the sequence. Usually this is all on one line, but you can see that this one is formatted so that each sequence line is only 80 characters wide. This makes it easy to read, but makes it slightly more difficult to search within the file. For searching, its nice to have files where all of each sequence is on a single line. For instance, lets see whether there are any EcoRI sites are in the Raphanus.fa file:

grep "GAATTC" Raphanus.fa

grep is a program that searches for any string, and by default returns the entire line that your string is found in. For a file this big, this isn't very helpful. So lets modify how grep reports it's findings:

grep -B 1 "GAATTC" Raphanus.fa

-B number grep will return the line with your string plus 'number' lines of 'before context', so here we'll get one previous line…the comment that tells us the sequence name

Now we know which of the sequences have the restriction site we're looking for, but there's so many they've overfilled the screen. So lets redirect the output from the screen into a file:

grep -B 1 "GAATTC" Raphanus.fa > Raphanus_EcoRI.fa

The greater than sign takes everything that happens on this side of it > and dumps it into the place designated here. So, all of the output from that grep command above got saved into a new file called Raphanus_EcoRI.fa

Since we didn't specify a place to save it, the new file is just saved in the same folder we're in, and we can see it by using ls again:

ls -lahr

-r makes the list print to our screen in reverse chronological order, so the newest files are on the bottom. This makes it easier to find what we're looking for.

grep, ls and head all have lots of useful flags, but we'll only do one more for now:

grep -c "GAATTC" Raphanus.fa

-c grep 'counted' 88 instances of EcoRI

SSF, FASTQ and FNA & QUAL files

SSF stands for Standard Flowgram Format and is for 454 data FASTQ is named after FASTA and is the output from most Illumina sequencers FNA for FASTA nucleic acid, and QUAL for quality. If you have Solexa data you might have these These are all files that you might get from your sequencing facility, and they all tell you about the machine, the sequence, and the quality of the sequence.

These are more complex than FASTA files, because they include quality information, but that often makes them more useful.

Most likely, you'll only be using FASTQ, as most people are doing Illumina sequencing right now.

head -4 33_20081121_2_RH2.fastq

FASTQ files have four lines of data per sequence.

Line one should look something like @30LWAAAXX_KD1_4:2:1:1428:1748 or @EAS139:136:FC706VJ:2:2104:15343:197393 1:Y:18:ATCACG depending on the vintage of your particular sequencer.

In either case, the jumble of letters between the @ and the first : are a unique instrument name. After that each of the numbers between the colons represents things like run ID, flowcell lane, physical coordinates of the cluster that sequence came from, and whether the sequencing was single or paired end. (See the Wikipedia to decipher your own.)

Line two is the sequencers calls based on light/ph/etc

Line three is often just a '+', but can be followed by some description

Line four are the quality scores for each base call, encoded as ASCII symbols

Probably the most confusing thing about FASTQ are the wide variety of quality scores that different sequencing companies have adopted. If you keep good records, including what type of machine each of your sequences was run on, and at what time, this isn't such a problem. However, if you've just inherited a pile of poorly managed sequences, you'll need your detective hat:

SSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSS.....................................................

..........................XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX......................

...............................IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII......................

.................................JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ......................

LLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLL....................................................

!"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]^_`abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz{|}~

| | | | | |

33 59 64 73 104 126

0........................26...31.......40

-5....0........9.............................40

0........9.............................40

3.....9.............................40

0.2......................26...31........41

S - Sanger Phred+33, raw reads typically (0, 40)

X - Solexa Solexa+64, raw reads typically (-5, 40)

I - Illumina 1.3+ Phred+64, raw reads typically (0, 40)

J - Illumina 1.5+ Phred+64, raw reads typically (3, 40)

with 0=unused, 1=unused, 2=Read Segment Quality Control Indicator (bold)

L - Illumina 1.8+ Phred+33, raw reads typically (0, 41)

(See complete image and much more discussion at Wikipedia)

Quality scores range from -5 to 40, on a somewhat overlapping range of ASCII encoded numbers, such that if your data happened to all have quality scores of 'F' and you didn't know how they were sequenced, it would be impossible to know whether 'F' meant the were all quality 38/40 from Sanger(which is quite good), or quality 6 from Illumina 1.5 (which is quite not good). In practice, you'll almost always have a good range of scores in your data, and by carefully comparing your quality scores to the chart above, you can usually work out where your documentation-challenged colleague got those samples they want you to analyze. (There's also a much easier way, which we'll get to at FastQC)

SAM and BAM

SAM files are tab-delimited files that describe how reads align to a sequence. They generally start with header lines (which always start with @) before the actual alignments.

BAM files hold all the same information, but in binary format, which makes them much faster for computers to use, but impossible for us to read. Lets check:

head 12724.bam

head 12724.sam

The .bam file just looks like nonsense, but the .sam file looks sort of like we expected, except its all headers. So lets look at more of the SAM file:

head -20 12724.sam

…hmm

head -100 12724.sam

…that's a lot of headers. Rather than try to guess how far the header goes, lets just look at the other end of the file:

tail -20 12724.sam

tail works just like head, except it counts up from the end of the file instead of down from the top. So now we can see an example of the alignment part of the file.The alignments all have at least 11 standard columns (although the values might be zero), but can have lots of extra ones as well. These are the 11 required columns:

| Col | Field | Type | Brief description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | QNAME | String | Query template NAME |

| 2 | FLAG | Int | bitwise FLAG |

| 3 | RNAME | String | Reference sequence NAME |

| 4 | POS | Int | 1-based leftmost mapping POSition |

| 5 | MAPQ | Int | MAPping Quality |

| 6 | CIGAR | String | CIGAR string |

| 7 | RNEXT | String | Ref. name of the mate/next read |

| 8 | PNEXT | Int | Position of the mate/next read |

| 9 | TLEN | Int | observed Template LENgth |

| 10 | SEQ | String | segment SEQuence |

| 11 | QUAL | String | ASCII of Phred-scaled base QUALity+33 |

Because SAM files are tab-delimited, they are easy for both people and computers to read, (just not as quickly as BAM files). For instance, we can use the program cut to get the flags from a SAM file:

cut -f 2 12724.sam

-f which 'field' do you want?

That was way too much stuff to look at. So lets make our first script! All we're going to do it take the output from tail and send it into cut using a program called 'pipe':

tail -20 12724.sam | cut -f 2

Now we have just the flags from the last 20 lines. Instead lets get the flags from the last 20 lines and their sequences:

tail -20 12724.sam | cut -f 2,10

Exercise 1: Get all of the integer type data from the last 30 lines

Exercise 2: Get the quality scores from the penultimate 10 lines

VCF

Variable Call Format contains the genotype information for variable bases in reads mapped to an alignment. Only variable sites are included.

Example:

##fileformat=VCFv4.0

##fileDate=20090805

##source=myImputationProgramV3.1

##reference=1000GenomesPilot-NCBI36

##phasing=partial

##INFO=<ID=NS,Number=1,Type=Integer,Description="Number of Samples With Data">

##INFO=<ID=DP,Number=1,Type=Integer,Description="Total Depth">

##INFO=<ID=AF,Number=.,Type=Float,Description="Allele Frequency">

##INFO=<ID=AA,Number=1,Type=String,Description="Ancestral Allele">

##INFO=<ID=DB,Number=0,Type=Flag,Description="dbSNP membership, build 129">

##INFO=<ID=H2,Number=0,Type=Flag,Description="HapMap2 membership">

##FILTER=<ID=q10,Description="Quality below 10">

##FILTER=<ID=s50,Description="Less than 50% of samples have data">

##FORMAT=<ID=GT,Number=1,Type=String,Description="Genotype">

##FORMAT=<ID=GQ,Number=1,Type=Integer,Description="Genotype Quality">

##FORMAT=<ID=DP,Number=1,Type=Integer,Description="Read Depth">

##FORMAT=<ID=HQ,Number=2,Type=Integer,Description="Haplotype Quality">

#CHROM POS ID REF ALT QUAL FILTER INFO FORMAT NA00001 NA00002 NA00003

20 14370 rs6054257 G A 29 PASS NS=3;DP=14;AF=0.5;DB;H2 GT:GQ:DP:HQ 0|0:48:1:51,51 1|0:48:8:51,51 1/1:43:5:.,.

20 17330 . T A 3 q10 NS=3;DP=11;AF=0.017 GT:GQ:DP:HQ 0|0:49:3:58,50 0|1:3:5:65,3 0/0:41:3

20 1110696 rs6040355 A G,T 67 PASS NS=2;DP=10;AF=0.333,0.667;AA=T;DB GT:GQ:DP:HQ 1|2:21:6:23,27 2|1:2:0:18,2 2/2:35:4

20 1230237 . T . 47 PASS NS=3;DP=13;AA=T GT:GQ:DP:HQ 0|0:54:7:56,60 0|0:48:4:51,51 0/0:61:2

20 1234567 microsat1 GTCT G,GTACT 50 PASS NS=3;DP=9;AA=G GT:GQ:DP 0/1:35:4 0/2:17:2 1/1:40:3

Pre-Header information

File meta-information is included after the ## string

The 'fileformat' field details the VCF format version number.

##fileformat=VCFv4.0

INFO fields

##INFO=<ID=ID,Number=number,Type=type,Description=”description”>

The Number entry is the number of values that can be included with the INFO field. For example, if the INFO field contains a single number, then this value should be 1. However, if the INFO field describes a pair of numbers, then this value should be 2 and so on. If the number of possible values varies, is unknown, or is unbounded, then this value should be '.'. Possible Types are: Integer, Float, Character, String and Flag. The 'Flag' type indicates that the INFO field does not contain a Value entry, and hence the Number should be 0 in this case. The Description value must be surrounded by double-quotes.

Each column in the body of the file should have an info field in the header.

The header line syntax

The header line names the 8 fixed, mandatory columns. These columns are as follows:

#CHROM

POS

ID

REF

ALT

QUAL

FILTER

INFO

If genotype data is present in the file, these are followed by a FORMAT column header, then an arbitrary number of sample IDs. The header line is tab-delimited.

- Data lines

Fixed fields

There are 8 fixed fields per record. All data lines are tab-delimited. In all cases, missing values are specified with a dot (”.”). Fixed fields are:

CHROM chromosome: an identifier from the reference genome.

ID semi-colon separated list of unique identifiers.

REF reference base(s): Each base must be one of A,C,G,T,N.

ALT comma separated list of alternate non-reference alleles called on at least one of the samples.

QUAL phred-scaled quality score for the assertion made in ALT.

FILTER filter: PASS if this position has passed all filters, i.e. a call is made at this position. Otherwise, if the site has not passed all filters, a semicolon-separated list of codes for filters that fail. e.g. “q10;s50” might indicate that at this site the quality is below 10 and the number of samples with data is below 50% of the total number of samples.

Non-Genomics Text Files

#### README, TXT, MD, HTML, R, Python & limitless others

There are lots of text file types that are not specific to genomics, but that you'll end up using all the time. These can have any format at all, and any file extension, the only stipulation is that they be written in ASCII text. The text your reading right now is a .md (markdown) file rendered as a .html (so you can read it online). All of them can also be opened in a text editor (like sublime). Technically, you can open just about anything in a text editor (like we did with the BAM file), but text format files can be meaningfully opened in a text editor. So if you have a new file, how do you tell what kind it is? The way we've been doing it is by opening each file and looking at them, but that won't always work. Once you have thousands of new files, you don't want to open each one and do an eyeball check. It's much better to let the computer do it for you:

file *

file is yet another program, and it does exactly what it sounds like, it tells you about files. The * is a 'wildcard', and works just like in playing cards. '*' specifically means 'any character', but there are more specific wildcards too, for instance we could ask for anything with a number in the name:

file *[0-9]*

Or anything that starts with a number:

bash

file [0-9]*

but for now, lets look at all of them:

file *

Now we can see that most of our files are ASCII text, that BAM files are actually gzipped, and lots of others.

An aside: lets look at AmandaSHellHistory.txt:

AmandaShellHistory.txt: ASCII English text, with CRLF line terminators

This one specifically points out the line terminators, that is, the invisible characters at the end of each line. For reasons not worth discussing, UNIX, Macs and Windows computers all use different invisible characters, and most of the time you can't tell the difference. If you open a file with UNIX line endings on your Windows machine, it will almost always look the way you expect, because most professional software can handle the difference seamlessly. Furthermore, most text files you get from a sequencing facility will have UNIX line terminators. However, some programs can't seamlessly handle unfamiliar line endings, and will display your text as if there aren't any (just one huge, never-ending line), which is a problem. And, if you open and edit text files on your Windows or Mac computer, some programs will save that file with the line endings that your operating system uses instead of UNIX ones, and that can cause all sorts of downstream problems as well. The take home lesson is that if a file looks right to you, but is giving you weird output, check the line endings.

Other File Types

CSV, XLS, XLSX

These files will all look the same when opened in Excel or a similar program, however they are very different when viewed from a text editor.

head Ex_combined.csv

head SeqProductionSumm.xls

When given the choice, it's usually best to save spreadsheet type data as a .csv, it won't keep formatting like colors and bolding, but it can be opened on just about any computer, and in any text editor. They also tend to be much smaller than the same data saved as an Excel file.

FASTQC

We've already seen FASTQC, but a FASTQC 'file' is actually a combination of two files: an .html and a .zip file. Generally the two files have the same name, and just different file extensions. The .html file is for viewing, and has all of the information about what the webpage should look like, but none of the actual data. This file is designed to look at in the GUI, not the command line, and looking at it with head will just show us html code.

All of the data is stored in the .zip file.

Exercise Unzip 64_20081121_2_RH2_fastqc.zip using the command line

Inside this file are mostly text files of summary data. Let's look at a couple of potentially useful ones:

unzip 64_20081121_2_RH2_fastqc.zip

cd 1_20081121_2_RH2_fastqc/

ls

less fastqc_data.txt

This file has all of the numeric data that goes into creating the images of the .html file. These are useful for making your own plots, or if you want to grep out, say, the quality of base 30 in all of your sequencing runs. Press q to exit less.

ls Images/

files Images/*

These are all PNG files, which is a type of image file. If we open it with head (or less, or more, or any other text reader), we get nonsense output:

head Images/adapter_content.png

However, if we look at these with the GUI, they correspond to all of the images in the html document. These are useful if you want images for presentations or similar uses, please DON'T take a screen-shot of the .html file in your browser, these are higher quality, and already there!

As mentioned above, FASTQC files can also be helpful if you don't know your sequence encoding. Just run the files through FASTQ. It checks through the above chart for you and makes it's best guess as to which encoding best fits your output, and it usually guesses pretty well. Lets look at an example. Here, we're going to look at the .html file in a browser, so use your normal file browsers to navigate to the Genomics folder we've been looking at, and click on 33_20081121_2_RH2_fastqc.html and in another window also open 64_20081121_2_RH2_fastqc.html These two files are exactly the same, except that I've (somewhat arbitrarily) changed all of the quality scores in the 64_20081121_2_RH2_fastqc.html to look like they came from a different kind of sequencer. However, you can see that FASTQC wasn't fooled, and shows us exactly the same graphs regardless.

Other file formats

This tutorial could never be a complete list; there are nearly as many file formats are there are bioinformatic packages, as everyone seems to invent their own. Most of the common ones are easily google-able, i.e. "bed file format", and the uncommon ones should at least be described in the documentation for the program that created them. Sequencing facilities are also often great resources for finding more information, UCSC , for instance, has a particularly good section on file formats.

Scripts for converting between file formats

Since most genomics files are just text, it's relatively easy to convert between them, and you could write your own file converter with a complicated enough find/replace command. However, LOTS of people have already written scripts that do this for you, and have made them available online. When you need to convert files, the easiest thing to do is simply Google the conversion, i.e. "sff convert to fastq", this will almost always give you many options to choose from. You can also ask at your sequencing facility, as they likely have already written scripts to convert their output to popular formats. Here's a couple links to groups that have made free conversion tools available for anyone to download: Bioinformatics at COMAV and khmer.

Now, some real data!

Download a reference genome from Ensembl

- Visit the Ensembl database at http://bacteria.ensembl.org/index.html. In the 'Search for a genome' search box search for 'Escherichia coli B str. REL606'; this should bring you to the genome of the strain used in the Lenski experiment (ensemble direct link)

- There will be a link 'Download DNA Sequence(FASTA)'. Click on the link and copy the URL from the web browsers navigation/location display (i.e. http://bacteria.ensembl.org/escherichia_coli_b_str_rel606/Info/Index).

- Use the

wgetcommand to download the contents of the ftp site (don't forget to use the '*' wildcard to download all files)

$ wget ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/bacteria/release-27/fasta/bacteria_5_collection/escherichia_coli_b_str_rel606/dna/*

You should have downloaded the following files:

CHECKSUMS

Escherichia_coli_b_str_rel606.GCA_000017985.1.27.dna.chromosome.Chromosome.fa.gz

Escherichia_coli_b_str_rel606.GCA_000017985.1.27.dna.genome.fa.gz

Escherichia_coli_b_str_rel606.GCA_000017985.1.27.dna_rm.chromosome.Chromosome.fa.gz

Escherichia_coli_b_str_rel606.GCA_000017985.1.27.dna_rm.genome.fa.gz

Escherichia_coli_b_str_rel606.GCA_000017985.1.27.dna_rm.toplevel.fa.gz

Escherichia_coli_b_str_rel606.GCA_000017985.1.27.dna_sm.chromosome.Chromosome.fa.gz

Escherichia_coli_b_str_rel606.GCA_000017985.1.27.dna_sm.genome.fa.gz

Escherichia_coli_b_str_rel606.GCA_000017985.1.27.dna_sm.toplevel.fa.gz

Escherichia_coli_b_str_rel606.GCA_000017985.1.27.dna.toplevel.fa.gz

README

-

Use the

lesscommand to examine theREADMEfile - in particular, look at thedefinition to understand what the differently zipped files are. -

Generate a checksum using the

sumcommand(sumis used by Ensembl and is an alternative tomd5sum) for theEscherichia_coli_b_str_rel606.GCA_000017985.1.27.dna.genome.fa.gzfile and compare with the last few digits of the sum displayed in the CHECKSUMS file. -

Preview the first few lines (

head) of the compressed (gzip'd) reference genome using thezcatcommand:

$ zcat Escherichia_coli_b_str_rel606.GCA_000017985.1.27.dna.genome.fa.gz | head

- Finally, unzip the E.coli reference genome, which will be part of the variant calling lesson and place it in your

datafolder in a newref_genomefolder.

$ gzip -d Escherichia_coli_b_str_rel606.GCA_000017985.1.27.dna.genome.fa.gz

Tip: create the ref_genome folder in ~/dc_workshop/data and use the cp command to move the data